Top Five!

Escape hatches from reality

If you’ve had a hard time focusing the past few weeks, I’m with you. I’ve needed so much time to recover from whatever the news is doing to me. I feel lucky I came across a book I became fully engrossed in about a month ago. It has been saving me from going any further with self-destructive, addictive behaviour on the internet. I finished it last night, and the whole experience reminded me of the importance of valuing and protecting the complexity of one’s humanity - the particular curiousity, preferences, imagination, opinions, etc. that make you, you - and refusing to be reduced to a neurotic entity that’s just there to react to the latest threat, worrying about survival.

A book is the best escape hatch for the consciousness in difficult times, though the more demanding I get over the years, the harder it is to unlock that magic with a piece of fiction. This time around the escape was The Balkan Trilogy by Olivia Manning, an underrated British writer of the 20th century, and it’s actually three novels published in one volume (reprinted by New York Review Books). I’m always talking about how I love a short book, but there is something so comforting and pleasurable about being so into what you’re reading and knowing you have 500-plus pages to go. It’s not ending any time soon. (This tome is 925 pages long!) The trilogy spans several years in the life of a newly married British couple at the outset of World War II. The husband is a lecturer in literature, posted to Bucharest, which is soon under threat of German invasion, and the couple eventually flees to Athens. It’s a chronicle of civilian life in wartime, an unsettling mix of the usual daily activity in cafes, stores, school and home, and the increasingly heavy cloud of incipient uncertainty, scarcity, upheaval, and violence. In this case the precarious feeling is heightened by the perspective of a foreigner in a bewildering new place, living in a small expat community. It felt like the right sort of parallel reality to escape to in 2025, not only because I felt in sympathy with the atmosphere, but also because it was a good reminder that historic, terrible times have been survived and followed by better times.

Lots more to say about these books (fascinating settings, lots of good characters, marriage as a central theme) but I mention it as it also prompted me to get off the sofa, wrap up my reading roundup and share my favorite reads of last year.

***

I didn’t include poetry in my summary this time around as I don’t enjoy writing about poetry (I always end up thinking it ends up speaking best for itself), but for the poets and poetry readers out there,* who will be curious (as I would be!) about what I did read, these are the poetry books I read in 2024, in alphabetical order by author:

Voyage of Uncle Hat, Tomas and Guido by Tomaž Šalamun, various translators from Slovenian, including Charles Simic (Arc Publications, 1997)

The Sonnets by Sandra Simonds (Bloof Books, 2014)

The Great Enigma: New Collected Poems by Thomas Tranströmer, trans. from Swedish by Robin Fulton (New Directions, 2006)

Crawlspace by Nikki Wallschlaeger (Bloof Books, 2017)

* I have a theory that 730 of regular of poetry readers are also poetry writers.

My favorite was the Tranströmer. Readers of poetry: tell me your favorite books published in recent years! Studying the above list, I realize I haven’t read a new and exciting book in some time. I have the newest books by Mary Jo Bang, Diane Seuss and Anne Carson on my to-read list, but I realize they are roughly in the same generation. I want to hear what the kids are up to…

As for fiction and nonfiction, here at last are my top five:

5. Role Play by Clara Drummond, translated from Brazilian Portuguese by Daniel Hahn (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2024, originally 2022)

A novella in the form of a monologue by a young, rich Brazilian woman who’s shaken by after witnessing a violent round-up of street vendors by the police. She takes stock of her life, her family, her sex life, friends, and career, fearing it doesn’t amount to much. It’s very much of our time, attuned to the anxieties and preening social media shows of the bourgeois and upper classes. The author balances satire and genuine feeling in her creation, and it’s quite funny at times. I suspect it has the potential to be much funnier in a better translation, but I suppose there’s no way to prove this until a better translation is published… My full review is at the Chicago Review of Books.

4. Parade by Rachel Cusk (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2024)

I’m actually surprised I ended up ranking this book so high on my list. It’s not one I would press into anyone’s hands or recommend casually, and it was her first in some time to receive negative reviews. I’ve recommended several of Cusk’s other books, but this one is for the heads only. However, her skill is such that even while having mixed feelings about this one (the last third was a real slog!!), there was enough material of interest to keep me thinking and reading. I found the first half or so to be exciting and the writing tremendous, in the mode of her Outline trilogy - dispassionate and mordant while at the same time insightful and asking complex questions about human relationships, gender, and art in a few pages. I’m also still puzzling over Cusk’s writerly decisions in this work - the structure, for example, and her insistence on never naming identifiable cities and well-known artists specifically, an apparent will to flatten everything into a hypothetical, general realm.

Almost every chapter tells the story of a different artist, all identified as “G”, offering a sketch of their life and art, and a central conflict. The chapters are never connected, except by theme, and I wondered if Cusk had some underlying plan or just said screw it and pulled together these various sketches/stories/profiles into one book and called it a novel. Some of the characters are amalgamations of real artists, some inventions, and some clearly directly taken from real life (Louise Bourgeois, Eric Rohmer). I read some reviews that stated that the book is better understood if you know something about the artists she bases her fictional portraits on, which just makes me think, why not just write an essay about them, naming them? Well, maybe I’m not making a good case for this book! But since each chapter is self-contained, I’d say it’s worth reading the first three chapters, at least, which are propulsive and brilliant.

3. Chéri by Colette (Fayard, 1920)

Colette was a big gap in my reading life. I made a start with Chéri, and am happy there’s a whole stack of her work ahead of me. This is the story of the end of an unexpected affair between Léa, a glamorous, rich courtesan in her 40s and Cheri, a 25-year-old, ravishing dandy, the son of one of her many frenemies. Léa has held the power in their years-long relationship but Chéri’s marriage to a lovely young girl and the incontrovertibility of Léa’s aging subverts their sensual, langorous idyll. It’s a fascinating power dynamic, particularly for the time. Chéri is often in the usual feminine position of restless pining, and Léa is the rational, unsentimental player. But of course sexist double-standards prevail, and a wrinkle in her neck is the source of destruction and dissolution. What I enjoyed most was Colette’s ability to transmit sensation, the sumptuousness of her character’s existence (fabrics, fragrance, lighting), and how much this material world was meaning itself for her characters. I read this in French, in a paperback edition from 1958 that belonged to my friend Richard’s mum, who was a French teacher. The blurb on the back just reads “Beaucoup plus qu’un histoire de gigolo” (Much more than the story of a gigolo.) Indeed!

2. The Gastronomical Me by M.F.K. Fisher (1943)

A memoir in the form of vignettes centered around experiences of eating and cooking. Sounds simple enough, but the book reveals how much is contained in those two acts. For Fisher they evoke memories of the people who fed her in childhood; food as a marker of travel and adapting to other cultures; learning to cook as an exercise in becoming an adult and a wife; cooking style as symbol of character; restaurant as a microcosm of society; eating alone as a declaration of strength; restaurant as a place of transformation (we’re talking about France here)… Fisher is, of course, the mother of all contemporary “food writing,” and after you read her, so much of it published today seems like feeble imitation. I found the structure of this book surprising, almost experimental for the time, in that she just drops you in on a scene, without giving any background on the setting or details on who anyone is. There are big gaps in years and much omitted about her life. It works, though, and several scenes are indelible to me. I think this is the last book that made me cry.

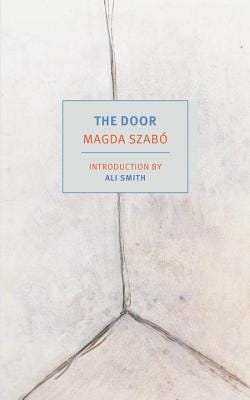

1. The Door by Magda Szabó, translated from Hungarian by Len Rix (New York Review Books, 2015, originally 1987)

I picked up this novel after seeing a few women rhapsodizing about it on lit Twitter (RIP) as a book that makes the world seem different after you read it. How could you not want to read it? I think it’s true. What an accomplishment. It’s about the friendship between a writer and an older woman who starts out as her housekeeper and becomes much more. It’s set in Budapest in the 1960s and 70s. Somehow, without pretension, with clarity and within 300 pages, it is also about the insidious, everlasting effects of war and trauma, mothers and mothering by those who are not mothers, animal intelligence and the meaning of love for animals, when to forgive and when not to forget, our responsibility to those we love as they age, the artist’s ego, and so much else that is difficult and moving about living and loving others. It sounds heavy, and I suppose it is, but not in a depressing way, more in a profound way, and it is also funny. The characters have so much substance and it also features one of the best dogs in literature.

***

Thanks for reading this dispatch amid all the other words flying around. Good luck out there, let’s not forget to keep reading books!

Postcript for anyone reading this far: I have tried out Storygaph as an alternative to Goodreads (for anyone looking to ditch Amazon platforms) and can confirm that transferring your data is easy. I haven’t explored the platform extensively, but it works fine for saving books read and books you want to read, which is mostly what I used Goodreads for…

Thanks as always for your cogent and thoughtful analysis and recommendations. You have captured so well the moment we are in and its debilitating impact. Reading is a wonderful remedy!